A BBC investigation has uncovered a network of fake social media accounts in Uganda. Under false identities, they spread pro-government messaging and target critics with threats. But who are the people behind it?

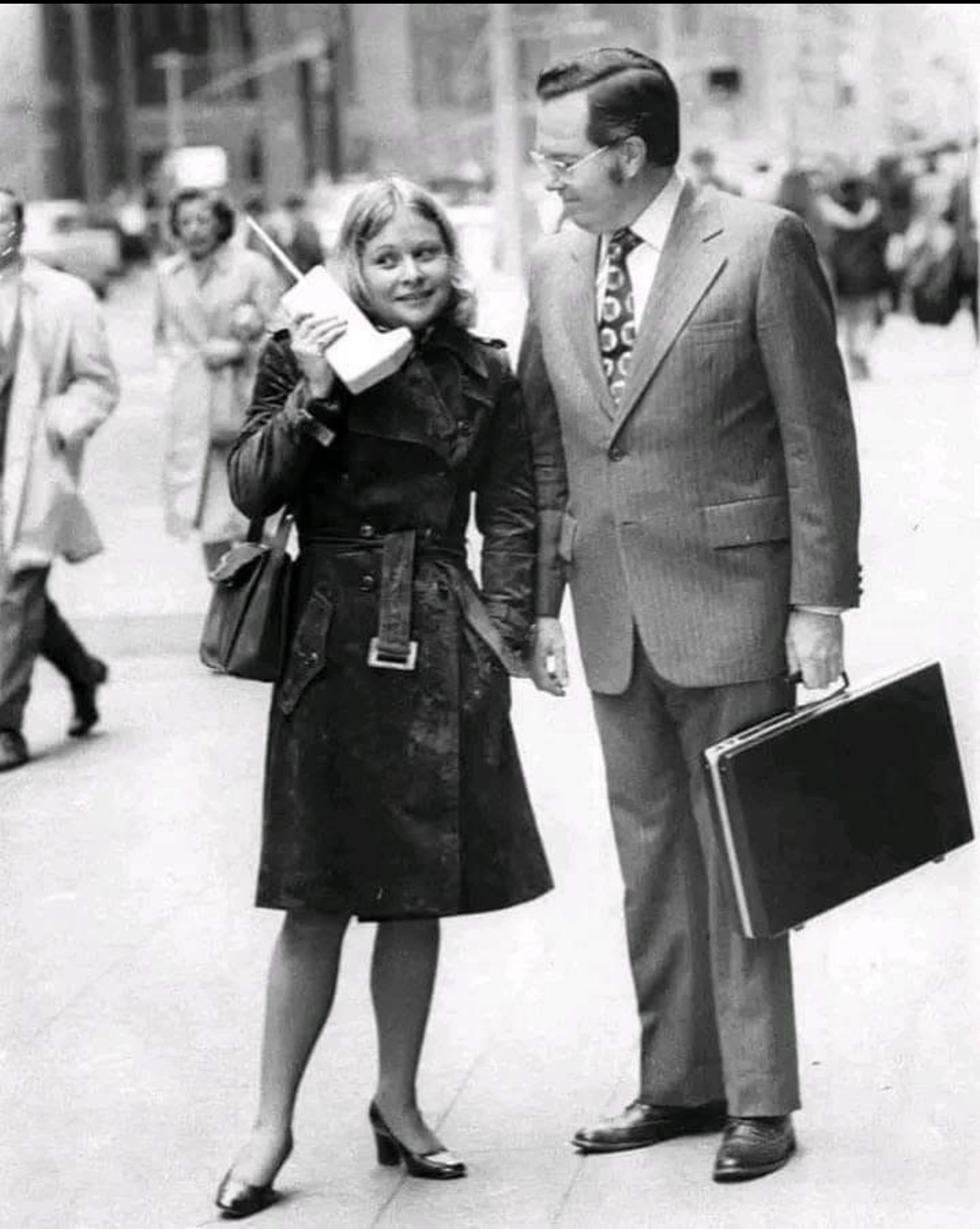

It is not every day that you get to take a selfie with the long-serving President of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni. When the opportunity arose, Dr Jamechia Hoyle went for it.

She is a senior consultant in the United States, focused on global health security. Back in October 2017, she had travelled to the Ugandan capital, Kampala, to attend an international conference.

Mr Museveni was there to welcome his foreign guests.

Making her way through the crowds, Dr Hoyle approached him, smartphone in hand. “He was really happy to engage with us and take the picture,” she recalls.

Seeing a broad-smiling Dr Hoyle and the president, surrounded by smiling faces trying to get in the shot, photographers couldn’t resist – and they too captured that image.

Four years later, this exact photo would be used to create a fake social media account aimed at spreading state propaganda and targeting government critics.

Dr Hoyle only recently found out about it, after the BBC got in touch with her.

“Seeing my own picture and then understanding the context of some of the things that were shared… I couldn’t believe it,” she says. “I was truly taken aback.”

‘Fake Jamechia’ steps in

The fake account using Dr Hoyle’s photo was created on X, then called Twitter, in October 2021.

From early on, it appeared to have no interests outside Ugandan politics, regularly posting in praise of the Ugandan government and its policies.

Much harsher words – including occasional threats – were directed at opposition supporters and government critics.

“We know you support terrorist activities”, the account posted without presenting any evidence, in response to a tweet from opposition leader Bobi Wine, whose real name is Robert Kyagulanyi.

“You will die”, read a separate tweet directed at Hillary Innocent Taylor Seguya, a Ugandan climate activist based in the US and a member of Mr Wine’s party, the National Unity Platform.

On social media, Mr Seguya has become known for his criticism of one of Uganda’s flagship projects: the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP).

When finished, the $3.5bn (£2.7bn) pipeline will connect Uganda’s oil fields to Tanzania’s port of Tanga, along a 1,445km (898 mile) route.

Supporters of the project say it will create thousands of jobs and generate millions in oil revenue.

But critics have argued that EACOP could prove disruptive for local communities, while having a significant impact on the environment.

“Trolls keep coming for me on a daily basis,” he says. “They keep labelling me as the enemy of progress in Uganda and Africa. Sometimes they call me a ‘US-backed puppet’ or a sell-out.”

The account belonging to “fake Jamechia” was just one of dozens attacking, harassing, and at times threatening Mr Seguya.

But, on closer inspection, the profiles all bore striking similarities to each other.

They all claimed to be Ugandan citizens – often women – whose accounts appeared to have the sole purpose of posting praise for the president and pushing back against critics.

The Ugandan Media Centre, which handles public communications on behalf of the government, did not respond to our requests for comment.

A sprawling network of fake accounts

By analysing those accounts’ behaviour, BBC Verify was able to map out a network of nearly 200 fake social media accounts operating on X and on Facebook (even though the latter has been blocked in Uganda since 2021).

The vast majority of these accounts used stolen images as profile pictures – often social media photos of models, influencers, and actresses from across the world. But none of the usernames used by them appeared to be linked to real individuals in Uganda or Tanzania.

These accounts often posted the same content within minutes of each other. By looking at the dates when they were created, we also found that many had been set up on the very same day.

This suggests that, while they may look like separate accounts, they have been working together.

It is unclear how successful this network may have been in actually shifting people’s views of the government, as very few of its posts earned large numbers of likes, comments, or shares.

For all its sophistication, could this network be failing to fulfil its mission then? Not quite, experts say.

“[Their] goal can be to push the message out there – whether or not people engage with it is kind of irrelevant, as long as people have seen it,” says Tessa Knight, a research associate for the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab who investigates disinformation.

Who is running this network of accounts?

Contacted by the BBC, Meta removed most of the Facebook accounts we identified.

Meta believes that individuals linked to the Government Citizen Interaction Centre (GCIC) – a Ugandan government agency – may have been running several of the accounts it removed.

The company did not share the evidence it said it held to back this assertion. And, as a result, the BBC has not been able to independently verify it.

But, in a statement, the GCIC denied this allegation, saying that agency accounts “are not operating on Facebook”.

And yet, it is not the first time the agency has been accused of running what Meta describes as “influence operations”: in 2021, Facebook’s parent company took action against hundreds of accounts it said were linked to the GCIC.

X did not reply to our requests for comment and the platform took no action against any of the accounts identified by the BBC’s investigation.

Asked whether it recognised any of the accounts on X, the GCIC said: “we recognise the accounts of our staff whose terms of reference include disseminating factual information about government programmes. We are only aware and responsible for accounts of our staff meant for work.”

The GCIC did not respond to follow-up questions attempting to clarify whether the accounts identified were indeed run by state employees.

Mr Seguya says he is “not surprised” by the existence of this network, but he urges whoever is behind it to consider the human cost of their campaign against critics.

“They may not know the negative impacts they are creating on someone’s mental health by sending out such threats to people like me and different activists.

“Let them not silence dissent. Dissent is democracy.”

NewLatter Application For Free