Watching al-Qaida Chief's 'Pattern of Life' Key to His Death

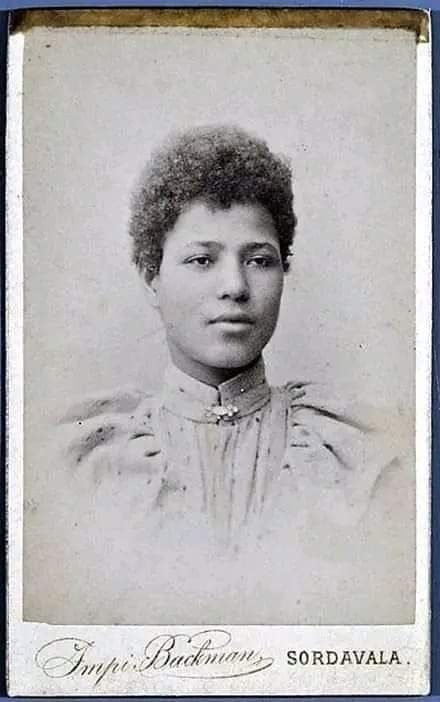

In this file handout picture released by the SITE Intelligence Group on Oct. 4, 2009 shows Ayman al-Zawahiri, the Al-Qaeda number two, giving a eulogy for Ibn al-Sheikh al-Libi.

U.S. officials had built a scale model of the safe house where al-Zawahiri had been located, and brought it into The White House Situation Room to show President Joe Biden. They knew al-Zawahiri was partial to sitting on the home’s balcony.

They had painstakingly constructed “a pattern of life,” as one official put it. They were confident he was on the balcony when the missiles flew, officials said.

Planning takes years

Years of efforts by U.S. intelligence operatives under four presidents to track al-Zawahri and his associates paid dividends earlier this year, Biden said, when they located Osama bin Laden’s longtime No. 2 – a co-planner of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the U.S. – and ultimate successor at the house in Kabul.

Bin Laden’s death came in May 2011, face to face with a U.S. assault team led by Navy SEALs. Al-Zawahiri’s death came from afar, at 6:18 a.m. in Kabul.

His family, supported by the Haqqani Taliban network, had taken up residence in the home after the Taliban regained control of the country last year, following the withdrawal of U.S. forces after nearly 20 years of combat that had been intended, in part, to keep al-Qaida from regaining a base of operations in Afghanistan.

But the lead on his whereabouts was only the first step. Confirming al-Zawahiri’s identity, devising a strike in a crowded city that wouldn’t recklessly endanger civilians, and ensuring the operation wouldn’t set back other U.S. priorities took months to fall into place.

That effort involved independent teams of analysts reaching similar conclusions about the probability of al-Zawahiri’s presence, the scale mock-up and engineering studies of the building to evaluate the risk to people nearby, and the unanimous recommendation of Biden’s advisers to go ahead with the strike.

Aim for accuracy

“Clear and convincing,” Biden called the evidence. “I authorized the precision strike that would remove him from the battlefield once and for all. This measure was carefully planned, rigorously, to minimize the risk of harm to other civilians.”

The consequences of getting it wrong on this type of judgment call were devastating a year ago this month, when a U.S. drone strike during the chaotic withdrawal of American forces killed 10 innocent family members, seven of them children.

Biden ordered what officials called a “tailored airstrike,” designed so the two missiles would destroy only the balcony of the safe house where the terrorist leader was holed up for months, sparing occupants elsewhere in the building.

A senior U.S. administration official, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss the strike planning, said al-Zawahiri was identified on “multiple occasions, for sustained periods of time” on the balcony where he died.

The official said “multiple streams of intelligence” convinced U.S. analysts of his presence, having eliminated “all reasonable options” other than his being there.

Two senior national security officials were first briefed on the intelligence in early April, with the president being briefed by national security adviser Jake Sullivan shortly thereafter. Through May and June, a small circle of officials across the government worked to vet the intelligence and devise options for Biden.

On July 1 in The White House Situation Room, after returning from a five-day trip to Europe, Biden was briefed on the proposed strike by his national security aides. It was at that meeting, the official said, that Biden viewed the model of the safe house and peppered advisers, including CIA Director William Burns, Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines and National Counterterrorism Center director Christy Abizaid, with questions about their conclusion that al-Zawahiri was hiding there.

Biden, the official said, also pressed officials to consider the risks the strike could pose to American Mark Frerichs, who has been in Taliban captivity for more than two years, and to Afghans who aided the U.S. war efforts who remain in the country.

U.S. lawyers also considered the legality of the strike, concluding that al-Zawahiri’s continued leadership of the terrorist group and support for al-Qaida attacks made him a lawful target.

The official said al-Zawahiri had built an organizational model that allowed him to lead the global network even from relative isolation. That included filming videos from the house, and the U.S. believes some may be released after his death.

On July 25, as Biden was isolated in The White House residence with COVID-19, he received a final briefing from his team.

Each of the officials participating strongly recommended the operation’s approval, the official said, and Biden gave the sign-off for the strike as soon as an opportunity was available.

That unanimity was lacking a decade earlier when Biden, as vice president, gave President Barack Obama advice he did not take – to hold off on the bin Laden strike, according to Obama’s memoirs.

The opportunity came early Sunday – late Saturday in Washington – hours after Biden again found himself in isolation with a rebound case of the coronavirus. He was informed when the operation began and when it concluded, the official said.

A further 36 hours of intelligence analysis would follow before U.S. officials began sharing that al-Zawahiri was killed, as they watched the Haqqani Taliban network restrict access to the safe house and relocate the dead al-Qaida leader’s family. U.S. officials interpreted that as the Taliban trying to conceal the fact they had harbored al-Zawahri.

After last year’s troop withdrawal, the U.S. was left with fewer bases in the region to collect intelligence and carry out strikes on terrorist targets. It was not clear from where the drone carrying the missiles was launched or whether countries it flew over were aware of its presence.

The U.S. official said no American personnel were on the ground in Kabul supporting the strike and the Taliban was provided with no forewarning of the attack.

In remarks 11 month ago, Biden had said the U.S. would keep up the fight against terrorism in Afghanistan and other countries, despite pulling out troops. “We just don’t need to fight a ground war to do it.”

“We have what’s called over-the-horizon capabilities,” he said.

On Sunday, the missiles came over the horizon.