Refusing to Stay Silent on Media Directives, Somali Journalist Goes on Trial

JOHANNESBURG —

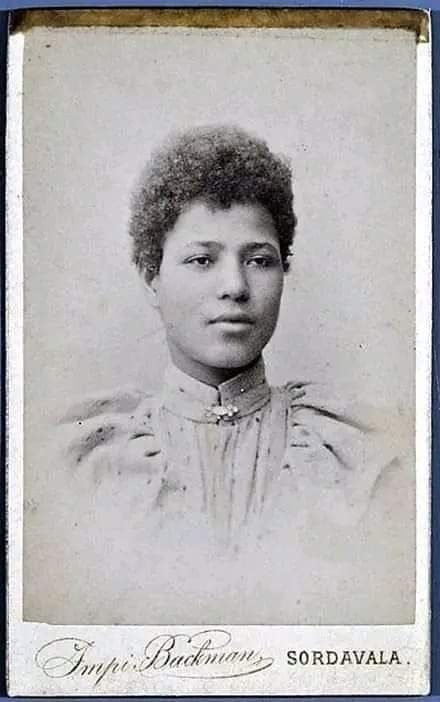

The old maxim that “the pen is mightier than the sword” couldn’t be more appropriate when it comes to Somali journalist Abdalle Ahmed Mumin.

As a child, Abdalle lost his arm in a militia attack. Determined to still write, he had to teach himself to do so with his left hand.

The clan fighting that maimed Abdalle killed his 11-year-old brother as the siblings walked home together from school.

At that time, the family were living in a refugee camp in Mogadishu, and the daily human rights violations and unfairness that Abdalle witnessed there set him on his career path as a journalist.

“Whenever there was food distribution the militia would come and loot that food and my mind was always asking me, when I grow up what can I do?” Abdalle told VOA. “Every day I used to buy a newspaper. I said, the best way to fight injustices is to become a journalist.”

But now the 37-year-old, whose work has appeared in international outlets including the The Guardian and The Wall Street Journal, is in his own fight for justice.

He is accused of publicly disobeying a government directive and holding a press conference that criticized the directive.

The Ministry of Information in a statement in October denied the charges are related to Abdalle’s work as journalist. But press freedom groups say the charges are spurious

Country in conflict

The case against Abdalle is linked with Somalia’s long battle with militancy.

Al-Qaeda-linked Islamist militant group al-Shabab has been waging a brutal insurgency for about 15 years. The militant group sees journalists who work for Western media as spies and often targets them.

In 2015, Abdalle survived an assassination attempt when militants shot at his car. He took his family and fled to neighboring Kenya, where they lived for several years.

Ultimately though, Abdalle couldn’t keep away from what he felt was his calling. He returned and helped form the Somali Journalists Syndicate (SJS).

Set up to defend the rights of working journalists, the independent trade union provides support and training, and is vocal in its defense of media rights.

Which is why it went into action in October last year when Somalia’s Ministry of Information published a directive that “prohibited dissemination of extremism ideology messages, both from official media broadcasts and social media.”

The ministry ban covered messages sent “intentionally or unintentionally, directly or indirectly and consciously or unconsciously.” Officials later told journalists to refer to al-Shabab as “khawarij,” which means “a deviation from Islam.”

The government said the directive was intended to stop the spread of al-Shabab propaganda, as U.S.-backed Somali forces battle the group, which regularly launches deadly attacks that kill hundreds of civilians every year.

While it is in the government’s remit to try to curb terrorist messaging, for the SJS and other media advocates, the vague wording raised concerns that the directive could be used to stifle independent reporting.

Somali Minister of Information Daud Aweis however believes journalists misunderstood the order.

“The journalists are free to do their job according to the law. What we only asked them is not to fall into the trap of al-Shabab, of spreading the hate and incitement propaganda of the terrorist group,” he told VOA via a messaging app.

When asked what role the government believes media could play in the fight, Daud — a former journalist who worked for outlets including VOA and the BBC — said, “Very simple, report objectively on these matters. That’s all what we need. Don’t be used as a tool of propaganda by the terrorists who are shedding the blood of Somali people, including the journalists themselves.”

Despite claims by the government that Somalia supports a free press, Abdalle says that in reality authorities want only military successes reported and nothing negative, like extra-judicial killings.

So, as secretary-general of the SJS, he called a press conference on October 10 and read a statement outlining concerns about the rules. After that, Abdalle says, his office was raided and he received a call from government asking that he retract the statement.

He refused.

The following day, Abdalle was arrested and taken to the National Intelligence Agency’s underground jail.

There, he says, he was interrogated without access to a lawyer. From his one-meter long cell he said he “could hear other inmates screaming.” He was later transferred to police custody and on October 16, a court released Abdalle on condition that he didn’t leave the country and didn’t speak to the media.

“But a journalist always speaks,” he said, adding that he refused a request by officials in the Ministry of Information to quit journalism and issue an apology in exchange for the case going away. Officials at the time denied to VOA such an offer was made.

Pressure from all sides

Somalia has long been a challenging place for journalists to work. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) considers the country one of the most dangerous in Africa for journalists, Muthoki Mumo, the group’s sub-Saharan Africa representative, told VOA.

“At least 73 journalists have been killed in connection to their work since 1992 and justice remains elusive in the majority of these cases,” she said.

Al-Shabab is responsible for many of these deaths, but Mumo said, “Government officials and security personnel whose responsibility it is to guarantee the safety of journalists, including by investigating attacks, also pose a threat.”

Journalists are frequently detained arbitrarily and intimidated by officials, she said. “Eight months into the presidency of Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, his government seems intent on using the fight against the al-Shabab as pretext to muzzle independent reporting and critical commentary.”

Mumo said the CPJ has heard that some journalists are avoiding reporting on certain stories because of the directive.

Somalia’s media for years have faced harassment, attack and persecution. Mohamed Odowa, a freelance journalist working for international press outlets in Mogadishu, says the environment has deteriorated over the past eight months.

Some journalists have “opted to leave the country for exile while others decided to remain home and keep in silent for fear of being harmed by the warring sides,” he told VOA. He said those who refuse bribes to write positive stories, face threats and harassment.

“The current government is trying to use independent media houses and journalists to cover the news related to the military operations in its favor,” he said.

Information Minister Daud rejects with such assessments on Somalia’s media environment, telling VOA, “We don’t want to see freedom of speech being violated at any cost.”

When asked about Abdalle’s case, he told VOA, “I would like to remind you that it’s not wise to comment on a case that’s before the court. Let’s allow the judiciary to do their job.”

Abdalle is due back in court Thursday. The case has shaken him.

Despite years of living in a war zone he said, this is the first time that he’s truly afraid: “I’m fearing for my life and I’m fearing for the lives of my colleagues, other journalists.”