Africa’s first heat officer is helping women keep cool in Sierra Leone’s capital Freetown.

At the start of Sierra Leone’s dry season in November, 26-year-old Adama Sesay sells fruits and vegetables at a busy market in the centre of the country’s capital, Freetown. It’s hard work, and one of the greatest challenges in her day is extreme heat.

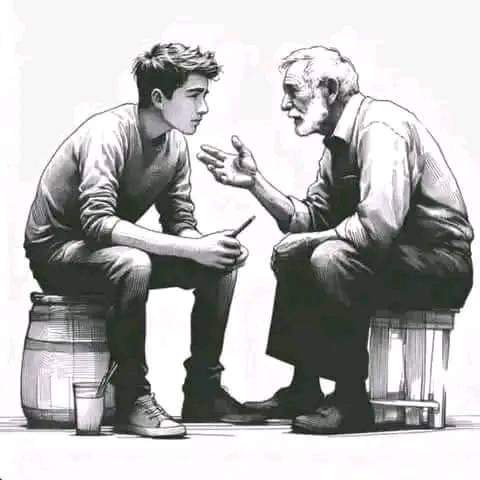

“We suffer from extreme heat, suffocation and noise pollution,” says Sesay, sitting on a cylinder brick in the overcrowded Bombay Street market, bustling with customers, traders, motorists and travelers.

“Sometimes the scorching Sun can be unbearable in the market,” she says. “We face frequent sweating, dehydration and headaches,” as well as heat rashes around her neck, back and shoulders.

Sesay is far from the only one. According to Freetown’s Climate Action Strategy, 94% of residents say the city was hotter in 2022 than it was five years ago and 82% report they are very sensitive to extreme heat.

ierra Leone is the 18th most climate vulnerable country in the world, according to the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index. The challenge is compounded by other environmental crises besides extreme heat – in 2017, a devastating landslide and floods affected more than 6,000 people and killed more than 1,000.

After the disaster, the government created a new Ministry of Environment and Climate Change responsible for environmental protection and climate adaptation and a National Disaster Management Agency to offer humanitarian assistance to disaster victims.

“The disaster sparked a nationwide revolution in the way residents view their environment, inspiring a nature-based local solution for Freetown’s climate change mitigation and adaptation,” says Freetown’s mayor Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr who has taken significant steps to make the capital more resilient to climate threats. She announced the city’s first climate action plan in 2022.

The women vendors in Freetown suffer from frequent headaches and dehydration due to extreme heat (Credit: Susan Kargbo)

The extreme heat doesn’t stop when market workers return home.

More than 30% of Freetown’s 1.3 million residents live in 60 informal settlements in the hills and coastal areas. Houses in these settlements are made of corrugated metal sheets that trap the intense heat.

Forty-five-year-old Mariama Bangura, a resident of Kroobay, one of the largest informal settlements in Freetown, says she uses a rubber fan to help cool her home.

Bangura lives with nine others, including three children, in a small living space without electricity, toilet or running water. Roughly 45,000 people live in Kroobay in such cramped conditions. During the summer, the average temperature reaches 29C (83F).

According to a dashboard set up by the non-profit World Resources Institute and EU project UrbanShift, 99% of Freetown’s built areas have low surface reflectivity, meaning they absorb heat and transfer it to immediate surroundings. This exacerbates a phenomenon known as the urban heat island effect.

The Freetown City Council plans to use the mapping project to track the effectiveness of several cooling projects aimed at helping vulnerable communities adapt to rising heat. (Read more about how community maps can protect children from extreme heat).

In 2022, Kargbo’s team and the Freetown City Council installed market shade covers to protect 2,300 street vendors. The shade covers, made from heat-reflective plexiglass, shield vendors from the scorching sun as well as heavy rain.

In addition to providing shade, the covers also include solar panels to harvest energy during the day. At night, these panels power lights, allowing the women to extend their working hours.

“We are now shielded, ensuring the safety of our goods and wellbeing,” says Sesay, who now works longer hours and earns a higher income.”The shade cover has improved my health and [allowed the] marketplace to adapt with the climate.”

Before the installation of the shade covers, street vendors would purchase beach umbrellas costing 400 and 500 Sierra Leonean Leone ($20-$25/£16-23) to shield them from the heat or rain, says Ya Alimany Forfonah, chair of the Congo Market.

We are now shielded, ensuring the safety of our goods and wellbeing – Adama Sesay

“The shade cover has eliminated the cost of buying a new beach umbrella every dry season, I can now spend some of that money on paying for rent, food and school fees for my two kids,” Sesay says.

She adds that the women sometimes still have to use their umbrellas as a heavy storm in August destroyed some of the shade covers. Kargbo says the council will replace all damaged covers and plans to install weather-resistant shades in the future.

“The installation of shade covers and solar street lights are smart ways of adapting to extreme heat exposure faced by street vendors,” says Edith Mamakoh Mbayo, a climate change adaption expert at the non-profit Young Green Women Sierra Leone.

“The shade cover benefits women the most in adapting to extreme heat, it provides them with a physical barrier from direct sunlight and excessive heat exposure,” says Mbayo. “Extreme heat can increase the risk of heat exhaustion, heatstroke, particularly pregnant women and those with pre-existing health conditions may be more vulnerable.”

A worker installs a reflective roof on a dwelling in Freetown, Sierra Leone, to help reflect heat away from the rooms below (Credit: Meer)

Kargbo and the city council are also implementing a cool roofs pilot programme in the informal settlement Kroobay. They are coating the roofs of 55 households, spanning a total of 1,200 sq m (3,937 sq ft), with a reflective mirror-like film to reduce indoor temperatures.

The project was carried out by the non-profit Mirrors for Earth’s Energy Rebalancing (Meer) which provides cooling solutions in India, Sierra Leone and in California. It was funded by Meer and the Freetown City Council.

Roofs installed with Meer’s mirror sheets were 15-20C (27-36F) cooler than older tin roofs during the day, according to Meer. In some instances, the organisation said indoor temperatures in buildings covered with a reflective mirror film fell by 6C (11F), compared with the interior of buildings without the cooling solution. However, Meer’s analysis has not yet been published or independently reviewed.

“The material is very reflective and therefore doesn’t absorb heat,” says Kargbo. “Sensors were installed on the roofs to test the level of cooling and the results are showing an amazing success.”

Kargbo says they are waiting for results from across the entire dry season. “Depending on its success and the availability of funding, we hope to roll the project out in other heat-trapped buildings across the city,” she says.

Bangura says the project is helping residents in Kroobay cope with the sweltering heat. “We can go to bed early and the children can now study at night, with the new roofing provided by the council for free,” she says.

Women are one of the most disadvantaged groups exposed to extreme heat – Eugenia Kargbo

The challenge is scaling up this innovation and introducing it in other informal settlements, says Kargbo. “We would need funding from the government and international partners, if the test is proven as the best solution.”

There are bigger changes at stake too, if the city is to stay cool in a warming world. Freetown urban planning urgently needs to be improved to increase ventiliation in dwellings, says Anthony Toban Davies, head of Ecosys, an environmental consultancy firm based in Freetown.

“Industries located in housing settlements in Freetown are also emitting extreme heat and pollution on inhabitants,” he says, adding that they should be relocated to a designated industrial zone in the city.

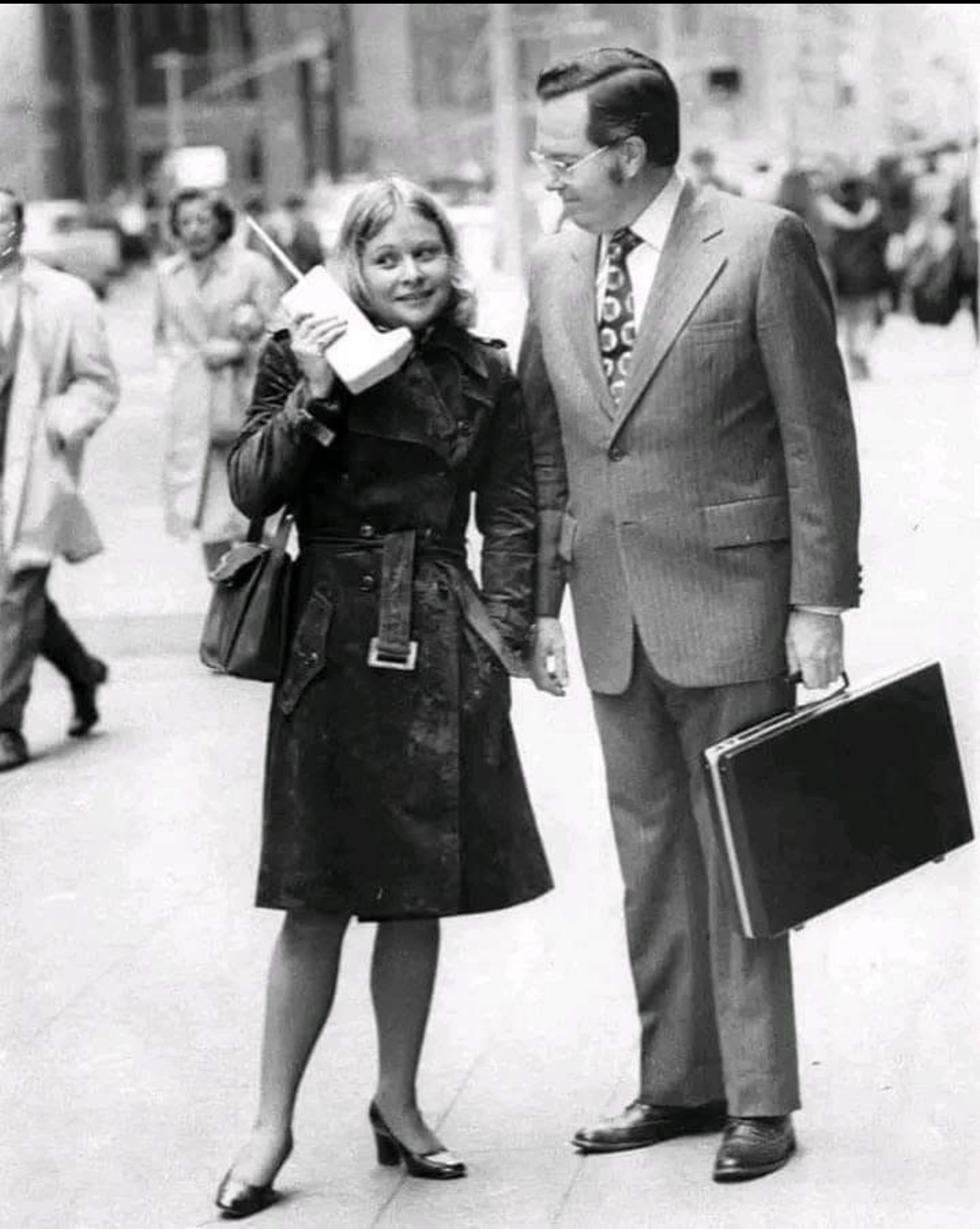

Elsewhere, the international team of heat officers have introduced a range of projects to help protect their citizens from rising urban heat. In Miami, the world’s first-ever chief heat officer Jane Gilbert worked with the city to designate May to October as official heat season and started using radio and bill boards to raise awareness about heat exposure. In Los Angeles, Marta Segura, has started naming, ranking, and categorising heat waves just like hurricanes.

In Santiago, Chile, Cristina Huidobro is overseeing a $2m (£1.6m) urban tree-planting programme to help cool neighbourhoods, and in Bangladesh, Bushra Afreenhas overseen the installation of water ATM booths, allowing people to access cheap drinking water in northern Dhaka.

Eugenia Kargbo is one of seven female heat officers appointed worldwide to help cities adapt to rising temperatures (Credit: Susan Kargbo)

Scaling up these heat-mitigating projects remains challenging. To date, shades have been installed in just three of Freetown’s 50 markets. Kargbo says the market shade covers and mirror roofs are both pilot projects and that the council plans to expand them depending on the results and availability of funds.

“We are still monitoring and analysing the benefits as we look out for the most suitable solution to overcome extreme heat exposure for our residents,” says Kargbo.

Currently Kargbo’s work relies heavily on international funding, adding to uncertainty about the projects’ long-term maintenance. “The challenge that we have is access to finance, to really scale up the work we are doing at city level,” she says.

“It’s very difficult to access climate adaptation finance not only for Freetown but for most of the cities in the Global South. Even though we contribute very little to global emissions, we suffer the most,” she adds.

Despite the heat officer’s efforts, Freetown remains highly vulnerable to rising heat. By 2050, climate change is expected to lead to 120 days, or four months every year, which are as hot as the 10 hottest days currently.

According to mayor Aki-Sawyerr, there are limits to Freetown’s capacity to adapt while temperatures continue to rise due to the burning of fossil fuels.

“We need fossil fuels to be stopped,” she says. “It’s the carbon from fossil fuels burning that is having the biggest impact on the warming and changing of our climate.”

But in the meantime, Freetown will continue to find ways to cope with the scorching temperatures.

“Funding climate change adaptation and the work of the chief heat officer means that you are providing the resources to ensure that people living in the most vulnerable and deprived spaces are safe and justice prevails,” says Kargbo.

“In the next couple of months, we will be publishing our heat action plan for the city to develop and build a model which can be replicated by other cities.”

This piece was updated on 13/11/2023 to clarify that roofs installed with Meer’s mirror sheets were 15-20C cooler than older tin roofs.

—

NewLatter Application For Free